It’s been quite a while since my last post as I have been focusing on other areas of my life. However, the current global pandemic and crisis have grounded airlines around the world. So I find myself with a bit more downtime than usual, especially since I’ve been self quarantined for 14 days after my last flight. I’m healthy, still employed (with a temporary salary reduction) and looking forward to getting back in the air soon.

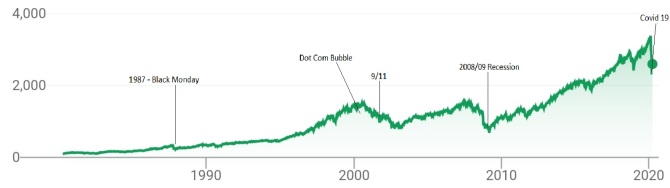

I was just remembering that my career started in the middle of the 2008/2009 financial crisis. And thinking back on the years before that, Black Monday in 1987 and 9/11 also shook Aviation and changed the world forever.

The important thing to remember now is, this too shall pass, like winter, this is an economic season of life and great opportunity is often borne from times such as this.

Yes, some airlines may collapse, pilots and crew will lose work and revenue and salaries will be lost. My heart goes out to everyone affected. Always remember; spring will return and we will rebuild. We will then probably see another 8 or 10 years of growth, before winter returns (another crisis) that will no doubt affect aviation once again.

Yes, some airlines may collapse, pilots and crew will lose work and revenue and salaries will be lost. My heart goes out to everyone affected. Always remember; spring will return and we will rebuild. We will then probably see another 8 or 10 years of growth, before winter returns (another crisis) that will no doubt affect aviation once again.

For now, I hope you stay positive, stay healthy and support your immune system while staying home. And let’s rewind to 2009, back to my first day of ground school.

Having graduated from the Academy with a brand new Commercial Pilot License (CPL), and Multi-Engine Command Instrument Rating (MECIR) in my wallet. I had a month or two back home with my parents to try not to forget what I’d learned in the last 10 months. Either way, basic flight training was over. I was ready, or at least due to start the first day of my new career as a Regional Airline Pilot.

I arrived on a Sunday in Albury, which was my first base, the day before I was scheduled to take the 6:30am flight to Sydney for ground school.

I was a nervous fish out of water. 21 years old at this point, and once again no idea what I was doing and feeling more than a little shy.

Sat in the terminal with my new F-COM (flight crew operating manual) in hand, trying to stick these Memory Items into my brain, with no understanding or context of what it all means. I had never been good at rote learning or memorisation. My strength is in understanding concepts, problem-solving and how things work. So in the short term, I suffer, but long term I tend to manage by developing a deeper understanding.

Sitting there at 6am on only 5hours of sleep, trying to memorise the unfamiliar sentences and figures from the book, trying to calm the nerves in my stomach.

“Power Lever: reduce to 20-30%”

” Condition lever: Torque motor lockout… ” wait, what the hell is a torque motor and how do I lock it out?… I’m so lost.”

The boarding announcement calls us to board, so I wander outside onto the tarmac behind the other passengers, where the Saab 340 is waiting. It is only the third time I’ve seen one in person, I quietly find my seat towards the back of the plane. It was a cold late autumn morning. Being the first flight of the day, my seat was freezing. I button up my jacket and pop the collar of my cheap suit trying to keep warm.

The last passenger to board the aircraft was sat across the aisle from me. A chirpy gentleman who spent the flight working on his laptop and seemed to know the flight attendant well. I got the impression that he might also work for the airline, or maybe just a regular passenger. Still feeling a little shy, like a kid on the first day of school, I decide not to introduce myself for the fear of looking stupid when he realised their newest pilot didn’t know a thing, and besides, he seemed busy. So I kept quiet and tried to catch up on some sleep during the hour flight instead.

Landing in Sydney I had to find my way to Regional Express Head Office, or “Baxter Road” as it was more commonly called. Still having No Idea about anything, and taxis refusing the short fare. I made my way there by walking the kilometer and a half wheeling my baggage behind me.

Finally, I am greeted with the familiar faces of my course mates from the pilot academy as I enter the classroom, as well as the face of the chirpy gentleman from the flight I’d just taken. Turns out, ‘Bugo’ as everyone calls him, is one of the nicest guys I’ve met, and he’s running our first few days of induction at ground school.

Now I was feeling stupid for not introducing myself and not getting some help to arrive at Baxter road.

I’ll try to summarise ground school best I can. It’s usually 5weeks or so of Induction, information sessions, technical lectures, studying and rote learning facts, figures, limitations, memory Items, scan flows, computer-based learning modules, exams, box-ticking and developing a caffeine addiction if you don’t already have one, since the tea and coffee station is the only relief from the monotony of a day under fluorescent tube lighting, and the awaited highlight of the day was the arrival of the famous coffee truck at about 11am. This brief experience has brought me some gratitude for dodging the 9 to 5 office job.

This was also my first time living out of a hotel room for an extended period of time, something I’d get used to.

As our ground instructor Simon would say… “The next few months will be like drinking from a fire hose”. He was right, the information never stopped flowing at high pressure. Things had stepped up a notch. Everything was faster, more intense and more professional with much higher expectations from what we saw at the academy. I didn’t have time to take a breath.

Rex at that point also didn’t have much experience in training pilots with such little experience. They typically hired Pilots with General Aviation experience and about 1000 hours.

To make things worse, my course was only the second group of cadets trained through the academy. So our standard after graduating from the academy was not consistently high yet or consolidated. We were left a little underprepared for the training to come and in need of a lot of extra polish. It was a steep learning curve for everyone. And I, as a somewhat naive twenty-one-year-old, had a lot of catching up to do.

However, I must say, in the following years, I saw a consistently high standard of cadets coming from the academy, and the transition became a lot smoother. Many pilots I had the pleasure of flying with and have seen them go on to make great careers as well.

A pretty good rule of thumb that I learned; is for a new job, don’t expect to have much of a life for at least six months after starting until you get competent. So much of your mental capacity will be used up, trying to settle into the new job and learn the ropes.

From the completion of ground school, we were headed for the Simulator. This is usually where training delays begin. Simulators are a finite resource, and they are notorious for breaking down.

For me, this was a welcome delay. The fire hose had been turned off momentarily. I was now left swimming in the overflow of information, and trying to drink a pool can be overwhelming. Especially when you don’t know, what you don’t know, and there is no guide or mentor to show you the way. Unlike high school, where you often have Teachers to hold your hand through the learning. I needed to learn how to study independently. It was to be a long road ahead.

If that question makes you a little anxious while you fly, don’t worry. You can keep sipping your champagne and relax, knowing that your Pilots have studied and trained hard to know where we are and where we are going, using accurate instruments and systems.

If that question makes you a little anxious while you fly, don’t worry. You can keep sipping your champagne and relax, knowing that your Pilots have studied and trained hard to know where we are and where we are going, using accurate instruments and systems.

I try to identify the big features and landmarks… A sinking feeling hit my stomach, “where the hell am I?” By now 17 minutes has passed since St Arnaud. The time ticking by faster and faster, with every minute, I’m travelling almost 2 nautical miles! Unlike a car, you can’t just pull over, look at the map and ask for directions. “Ok, I’ve been trained for this” I begin to retrace my steps like someone who had lost their keys. “I’m sure that was St. Arnaud where I turned onto a heading of 176 degrees, which is south…. South”, I looked at the map again… Maryborough isn’t south of Saint Arnaud… It’s south-east! I pull out my protractor, “136 degrees!” I had written the wrong heading on my flight plan!

I try to identify the big features and landmarks… A sinking feeling hit my stomach, “where the hell am I?” By now 17 minutes has passed since St Arnaud. The time ticking by faster and faster, with every minute, I’m travelling almost 2 nautical miles! Unlike a car, you can’t just pull over, look at the map and ask for directions. “Ok, I’ve been trained for this” I begin to retrace my steps like someone who had lost their keys. “I’m sure that was St. Arnaud where I turned onto a heading of 176 degrees, which is south…. South”, I looked at the map again… Maryborough isn’t south of Saint Arnaud… It’s south-east! I pull out my protractor, “136 degrees!” I had written the wrong heading on my flight plan!